Image

From TheMinuteman.org - It began on a decidedly crisp December morning, when the Federal Reserve — the Fed — announced that it would cut its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points (0.25%), lowering the target range to 3.50 %–3.75 %.

The decision was not unanimous — dissenters within the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) argued for no change, while some even pushed for a deeper cut.

What drove this moment? And why does a few decimal points in an interest-rate announcement feel like a watershed for millions of Americans?

To understand, we need to trace the idea of interest rates — what they are, how the Fed uses them, and how tweaks ripple through the economy like ripples in a pond.

Chair Powell answers interest rate questions at the FOMC press conference on November 7, 2024. (flickr)

Chair Powell answers interest rate questions at the FOMC press conference on November 7, 2024. (flickr)In the United States, the key benchmark of monetary policy is the Federal funds rate — the rate at which banks and credit unions lend reserve balances to each other overnight. These reserve balances are held at the Fed itself. The “effective federal funds rate” is the median interest rate of these daily interbank overnight loans, published every business day by the New York Fed.

But the Fed doesn’t just sit back and watch this rate float — the FOMC sets a target range. To hit that target, the Fed uses a variety of tools. It might adjust the interest it pays banks on reserve balances (the “interest on reserve balances,” or IORB), offer reverse repurchase agreements, or engage in open market operations — buying or selling government securities to influence how much cash is in the banking system.

In essence: the Fed steers a short-term interest rate — but one that ripples far beyond just overnight loans between banks.

The federal funds rate has been anything but static. Over the decades, it has swung dramatically depending on economic conditions. For example:

Thus, the rate cut we just witnessed is part of a long, rhythmic cycle — based on how the Fed judges the economy’s strength or weakness.

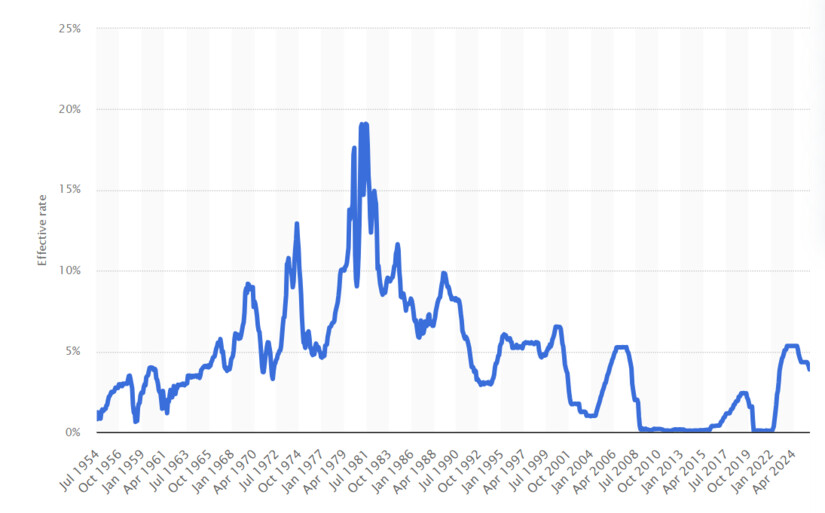

Monthly Federal funds effective interest rate in the United States from July 1954 to November 2025. © Statista 2025

Monthly Federal funds effective interest rate in the United States from July 1954 to November 2025. © Statista 2025The rate-setting by the Fed isn’t random. The FOMC makes changes with a dual mandate: to aim for stable prices (i.e., moderate inflation) and maximum sustainable employment.

In short: interest rate changes are a primary way the Fed tries to steer the economy — either slowing it down or giving it a push when needed.

When the Fed lowers the federal funds rate, the effects reverberate:

Conversely, when interest rates rise: borrowing becomes more expensive, which can slow spending and investment — but savers see better returns on savings and bonds, and lenders can charge more.

In short: rate changes carry winners and losers across different parts of the economy.

Lower interest rates often aim to stimulate growth — and thereby lift economic indicators like employment, output, business investment, and consumer spending.

But there are trade-offs. If borrowing becomes too cheap for too long, demand may surge so much that prices start climbing too fast — inflation can accelerate. Too much cheap money can also push investors to take on excessive risk, inflating asset bubbles.

On the financial markets side: as interest rates fall, bonds — especially longer-term ones — often increase in price (since their fixed payments become more attractive relative to new, low-yield bonds). Equities tend to benefit too, because lower rates reduce financing costs for businesses and make stocks more attractive compared with low-yield bonds.

But there is a timing dimension: some parts of the economy — like stocks — may react quickly; others, like home-buying or business investments, may take months to feel the impact.

Back to that December rate cut: it’s the third time in 2025 that the Fed has lowered interest rates, with cumulative reductions since 2024 amounting to a significant shift.

Analysts view this as a “risk-management cut” — not because the economy is collapsing, but because the data is murky. Inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target, yet the labor market shows signs of cooling. By cutting rates now, the Fed hopes to steady the ship: encourage borrowing and investment enough to support jobs, but without igniting runaway inflation.

Still, the Fed signaled caution: some members opted not to cut rates, signaling that this may not be an open-ended easing path. Markets reacted swiftly: stocks climbed, bond yields on short-term debt dropped — a sign that investors expect more favorable borrowing conditions ahead.

Yet, there are warnings in the room. If the Fed cuts too much or for too long, the risk is that inflation could bounce back, or asset bubbles could form.

When the Fed adjusts interest rates, it isn’t doing it for economists or Wall Street alone — it impacts how we live, borrow, invest, and build for the future. Lower rates can mean more affordable mortgages, cheaper business loans, perhaps easier credit for that new car or expansion of a small business. On a macro level, lower rates can support hiring, encourage investment, and help the economy avoid a descent into recession.

For markets, lower rates can fuel a rally in stocks and push bond prices up. But for savers, retirees, or conservative investors depending on fixed-income returns, it may mean less yield — requiring adjustments.

And for the economy at large, rate decisions by the Fed represent balancing acts: between promoting growth and guarding against inflation, between supporting jobs and preventing asset bubbles, between encouraging spending and preserving the long-term value of money.

The latest rate cut by the Fed is a chapter in a long story of economic cycles, monetary policy, and human behavior. It reflects current concerns — softening job growth, sticky inflation, economic uncertainty — and hopes for smoother waters ahead. Whether this move ushers in renewed growth, bubbles, or moderation depends on what unfolds next: how businesses and households respond, how global conditions evolve, and how the Fed reads and reacts to fresh data.

For now, many Americans may feel relief — perhaps their mortgage becomes a bit cheaper, or a business loan more accessible. But the long-term effects, both good and risky, remain to be written.

This article is from TheMinuteman.org, Morristown Minute's new partner site: Bringing Meaning Back to the News.