Image

From TheMinuteman.org - In the last few weeks, the “health care costs” debate stopped being abstract again. People shopping for coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have been staring at a cliff: the enhanced federal help that lowers many marketplace premiums is set to expire at the end of 2025, and families are already bracing for premium shocks in 2026.

That looming deadline also collided with Washington’s most familiar ritual—funding fights that spill into shutdown threats. A recent shutdown lasted 43 days, and one of the flashpoints was what to do about the ACA subsidy extension.

So if you’re wondering, “Why is it this hard to keep coverage affordable—and what would actually fix costs long-term?” here’s the story, in plain English.

The ACA created marketplaces (sometimes called “exchanges”) where individuals and families can buy private health insurance. Many shoppers qualify for premium tax credits—federal help that lowers the monthly premium.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress made those tax credits more generous and expanded who qualifies. Those enhanced credits are set to expire at the end of 2025 unless Congress extends them again. Researchers and insurers warn that ending them could raise premiums sharply and push people out of coverage.

You can see the human version of that policy sentence in recent reporting: people describing plans “practically doubling,” postponing home-buying or starting a family, and even considering going uninsured because the math stops working.

States are scrambling, too. Colorado, for example, held a special session and passed a measure aimed at softening the blow—essentially emergency state-level help because federal help may disappear. But even supporters describe these as temporary patches, not a substitute for the federal scale.

That’s the setup. Now the bigger question:

The United States isn’t just “a little” expensive—it’s in a different league.

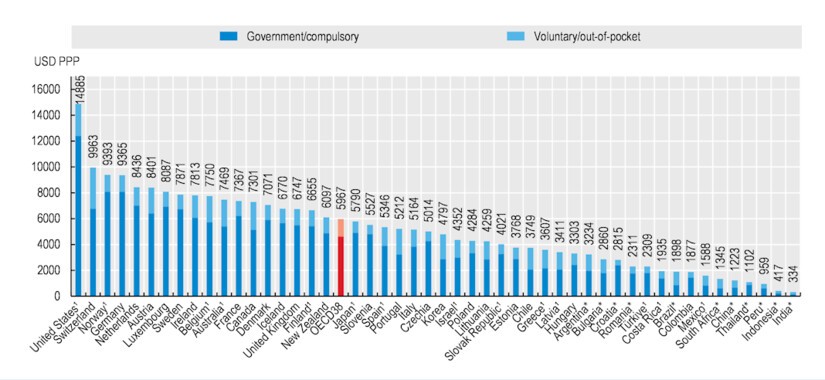

Health expenditure per capita, 2024 [OECD Health Statistics 2025; WHO Global Health Expenditure Database]

Health expenditure per capita, 2024 [OECD Health Statistics 2025; WHO Global Health Expenditure Database]The simplest explanation: we pay higher prices for the same kinds of things—hospital care, procedures, physician services, and many drugs—and we run a system with a lot of expensive complexity.

When hospitals buy up competitors or physician practices, they can negotiate higher prices with insurers. Harvard health economist Meredith Rosenthal points to consolidation (bigger systems with more leverage) as a major threat to affordability.

America’s patchwork of insurers, billing rules, and paperwork adds a layer of administrative spending that doesn’t treat anyone. A 2023 review describes U.S. administrative health care spending as roughly $1 trillion annually.

(That doesn’t mean it’s “easy” to cut—but it tells you where the bulk is.)

One example policymakers target is “pay-for-delay”: deals where brand-name drug companies pay generic manufacturers to delay launching a cheaper alternative. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has long argued these deals can block competition and keep prices high.

High deductibles and complicated cost-sharing can make people “insured” but still unable to afford health care—leading to delayed treatment, medical debt, and worse health later (which becomes higher cost later). Harvard researchers describe this affordability squeeze as a public health problem, not just a budget problem.

In traditional fee-for-service payment (meaning health care providers get paid for each service), the system can unintentionally reward doing more—even when “more” isn’t better.

Rally in Support of the Affordable Care Act, at The White House, Washington, DC USA

Rally in Support of the Affordable Care Act, at The White House, Washington, DC USAAffordable Care Act (ACA): The 2010 law that expanded health care coverage through marketplaces, Medicaid expansion (in participating states), and rules for private insurance.

Premium tax credits (ACA subsidies): Federal help that lowers the monthly cost of marketplace plans for eligible people.

Out-of-network: A doctor or facility that does not have a negotiated contract with your insurer—often leading to much higher bills.

No Surprises Act: A federal law (effective January 1, 2022) that can protect consumers from certain “surprise” out-of-network bills—especially in emergencies or when you didn’t have a real choice of provider.

There isn’t a single magic lever. But there is a realistic package of reforms that, together, can bend health care costs down while protecting coverage.

Think of it as four lanes on the same highway:

These don’t solve every root cause—but they prevent immediate harm.

This is where the big health care savings live—because prices drive so much of total spending.

This is the unglamorous stuff that can still save real money.

A reminder: researchers estimate administrative health care spending is enormous in the U.S., on the order of $1 trillion per year. You don’t have to “solve” all of that to save big.

You can frame the big system choices like this:

There’s no global consensus on the “one true model,” but the evidence is clear on one point: if prices and market power aren’t addressed, costs stay high—no matter who writes the checks.

Systematic health care reform matters more than shopping tricks. Still, there are a few practical moves that can reduce your risk:

If the enhanced ACA subsidies expire at the end of 2025, millions of people are likely to feel it quickly—through higher premiums, dropped coverage, or impossible household tradeoffs.

But the deeper fix to health care costs is bigger than subsidies: lower prices, reduce monopoly power, simplify administration, and pay for value instead of volume—while keeping coverage stable enough that people can actually use care before it becomes a crisis.

Want to learn more about healthcare?

This article is from TheMinuteman.org, Morristown Minute's new partner site: Bringing Meaning Back to the News.