Image

From THE MINUTEMAN.ORG - On a winter morning in Manhattan, Nicolás Maduro stood in a U.S. courtroom and said, in effect, I’m still the president of my country. His appearance came after U.S. forces seized him in Venezuela and brought him to New York, an operation Maduro’s team has called a kidnapping.

The U.S. says he is a defendant, flown in after a military operation that seized him in Venezuela and brought him to New York to face long-running narcotics and weapons allegations.

Back in Caracas, his vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, has been sworn in as interim president, while allies and adversaries argue over whether the raid was lawful, whether it was “kidnapping,” and what it means for the rules that govern relations between states.

This is the kind of ending that makes people rewrite the beginning. It invites a simple story: strongman falls, era ends.

Venezuela rarely cooperates with simple stories.

To understand Maduro, you have to understand how a handpicked successor turned a legacy into a system, how that system survived sanctions, protests, international isolation, and economic ruin, and how a country with the world’s largest proven oil reserves could become a place millions felt they had to flee.

You also have to understand that different groups, including Venezuelans themselves, disagree sharply about what caused the collapse, who bears what responsibility, and what comes next.

Hugo Chávez

Hugo ChávezMaduro’s biography is part of his political armor: he came from a working-class background, worked as a bus driver, and entered politics through union activism.

In Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, those details were not just trivia. They meant legitimacy.

Chávez rose by promising to upend an old order that many Venezuelans saw as corrupt, unequal, and captured by elites. He built what he called the Bolivarian Revolution, centered on state power, redistribution, and a populist bond with “the people,” financed by oil.

Maduro rose inside that world as a loyal operator: legislator, legislative leader, foreign minister, then vice president. He was not the magnetic figure Chávez was. But he was the one Chávez trusted, and that mattered when Chávez died, and the movement needed continuity.

Maduro won a razor-thin election in 2013. From the start, the question hanging over him was the one that haunts many successors: is he the heir or the placeholder?

His answer, over time, became less about persuasion and more about control.

Venezuela’s modern state is an oil state. Oil revenue does not just fund the government. It shapes everything: the currency, imports, the political bargain between rulers and ruled, and the temptation to treat elections as a referendum on who gets to distribute the rent.

When oil prices are high, that bargain can feel stable. When prices fall, or production collapses, the state’s promises become IOUs.

By the time Maduro took over, the model was stressed. Then the shocks compounded.

The result was an economic collapse that, for ordinary people, took the form of empty shelves, wages that evaporated, and a daily life reorganized around scarcity.

When economies break, politics tends to polarize. In Venezuela, it is also institutionalized.

Large protests erupted in waves, notably in 2014 and 2017, and the state response became a defining feature of Maduro’s rule: arrests, heavy-handed security tactics, and an expanding role for intelligence and security forces in managing dissent.

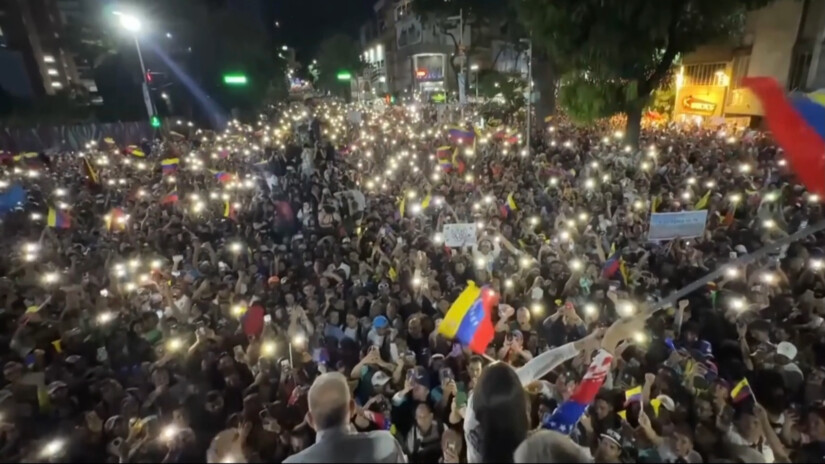

Protesters clash with the National Guard on the Las Mercedes bridge on June 7, 2017, in Caracas, Venezuela.

Protesters clash with the National Guard on the Las Mercedes bridge on June 7, 2017, in Caracas, Venezuela.International human rights bodies and investigators have described patterns of abuse and repression tied to state institutions. The U.N. Human Rights Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela has reported on state repression mechanisms and restrictions on civic and democratic space.

These concerns did not remain merely diplomatic talking points. The International Criminal Court opened an investigation into alleged crimes against humanity related to events since at least 2017, and ICC judges have authorized the prosecution to continue.

Maduro’s government rejects the premise, describing many international accusations as politicized. But the investigation itself is a sign of how far Venezuela moved from being a regional political dispute to being treated as a potential international crimes case.

A key reason Maduro endured is that Venezuelan politics stopped producing widely accepted results.

In 2015, the opposition won the National Assembly, and Venezuela entered a grinding constitutional struggle over who truly held power. Courts and electoral authorities aligned with the executive moved to limit the legislature’s authority, and alternative institutions were created or empowered in ways the opposition and many international observers said undermined democratic checks.

Maduro’s 2018 re-election was widely contested internationally, with regional bodies such as the Organization of American States taking steps to reject the legitimacy of his new term.

In 2019, opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president, and the United States and dozens of other countries recognized him. Over time, that effort lost momentum, and key international supporters scaled back recognition as the opposition dissolved the interim arrangement.

Then came the 2024 presidential election, the event that many Venezuelans believed would finally settle the legitimacy question.

Instead, it intensified it.

Election campaign for the 2024 Venezuelan presidential election

Election campaign for the 2024 Venezuelan presidential electionThe Carter Center said the 2024 election did not meet international standards of electoral integrity and that it could not verify the announced results, citing the failure to provide disaggregated polling-station data. The European Union similarly pointed to a lack of substantiation and concerns flagged by observers.

At the same time, a smaller election-observation delegation from the National Lawyers Guild reported it did not observe fraud or serious irregularities in the polling centers it visited. That does not resolve the dispute, but it matters because it shows how different observers, with different access and methods, can produce sharply different conclusions.

The broader takeaway is grimly consistent: Venezuela’s elections became less a mechanism to transfer power than a battleground over whether power can be transferred at all.

If Maduro’s legitimacy crisis was political, his durability was economic and geopolitical.

The United States and others imposed layers of sanctions over the years. U.S. policy shifted between pressure and conditional relief, including a period of eased measures tied to electoral commitments negotiated in 2023 and then tightened again when the U.S. said commitments were not met.

Sanctions became one of the most contested questions in the entire Venezuela story because they sit at the center of two competing explanations:

Explanation one: Venezuela collapsed because of corruption, mismanagement, authoritarianism, and the hollowing out of institutions. Sanctions, in this view, may have worsened an already failing state, but they did not cause the failure.

Explanation two: Sanctions, especially financial and oil-related restrictions, sharply accelerated the collapse by cutting off credit, complicating oil sales, and limiting the state’s ability to import essentials, making ordinary people pay the price for a political strategy.

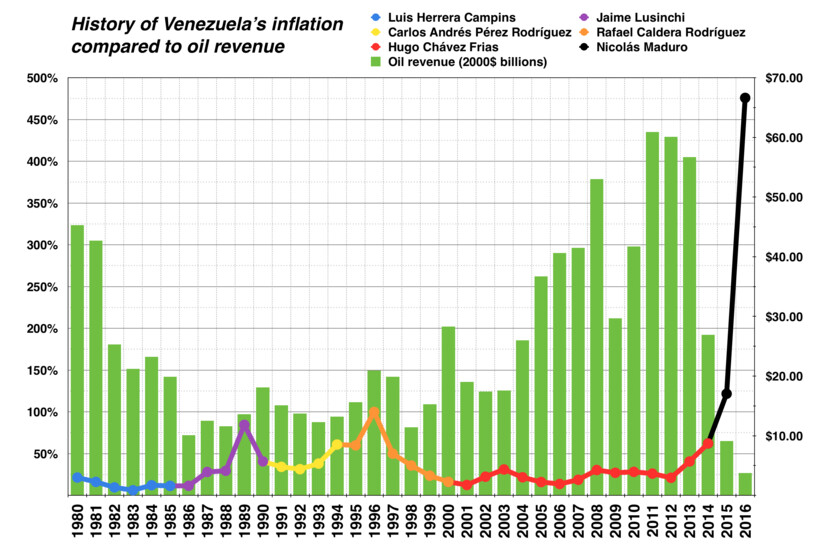

Historic rates of inflation and oil revenues in Venezuela from 1980 to the present. [Wikimedia Commons]

Historic rates of inflation and oil revenues in Venezuela from 1980 to the present. [Wikimedia Commons]There is evidence supporting parts of both arguments.

This is not a technical debate. It changes how people judge responsibility, morality, and policy.

If sanctions were primarily a tool that punished the regime, then tightening them feels like accountability. If sanctions were primarily a tool that punished the population while the regime adapted, then tightening them looks like collective punishment without strategic gain.

In practice, Maduro’s government survived. Venezuelans did not.

Numbers do not fully capture economic trauma, but Venezuela’s inflation story is still staggering.

By the late 2010s, the country experienced hyperinflation on a historic scale, with outside estimates reaching extreme levels and the International Monetary Fund estimating 2018 inflation in the hundreds of thousands of percent.

Hyperinflation is not just “prices going up.” It is the destruction of planning. Savings become meaningless. Salaries become jokes. People pay quickly because money decays. “Tomorrow” becomes a risky concept.

That is how an economic crisis becomes a social crisis. It rearranges families, pushes people into informal markets, and turns the state into either a lifeline or a predator, depending on who you are and what you can access.

The most visible measure of Venezuela’s collapse is that millions of Venezuelans left.

Hundreds of Venezuelans in transit are waiting in line at the customs office in Ecuador to have their passports stamped and continue their journey. In August of 2018, between 3,000 and 7,000 Venezuelans entered Ecuador daily, most of them en route to Peru. [Wikimedia Commons]

Hundreds of Venezuelans in transit are waiting in line at the customs office in Ecuador to have their passports stamped and continue their journey. In August of 2018, between 3,000 and 7,000 Venezuelans entered Ecuador daily, most of them en route to Peru. [Wikimedia Commons]Regional coordination platforms tracking displacement report nearly seven million Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean as of late 2025.

That number is not just a statistic. It is a political fact that reshaped neighboring countries, strained border regions, and turned Venezuela into a regional humanitarian and governance issue, not simply a domestic one.

It also became a source of leverage. Migration pressures often change how foreign governments calculate costs and risks, and Venezuela’s diaspora became a living referendum on Maduro’s rule.

For years, the U.S. framed Maduro not only as an authoritarian leader but as the head of a criminal enterprise.

In 2020, the U.S. Justice Department charged Maduro and other current and former Venezuelan officials with narco-terrorism, corruption, drug trafficking, and other offenses. Maduro denied the allegations.

This week, the legal storyline moved from press conferences and wanted posters to custody and court dates.

Reuters and other outlets report that Maduro pleaded not guilty in Manhattan federal court, calling the operation that brought him there a kidnapping. The Justice Department has released an indictment that alleges a long-running scheme involving drug trafficking and state protection.

The underlying allegations are not new. What is new is that the U.S. chose to enforce them through military force, and that is where the story stops being purely about Maduro and becomes about international order.

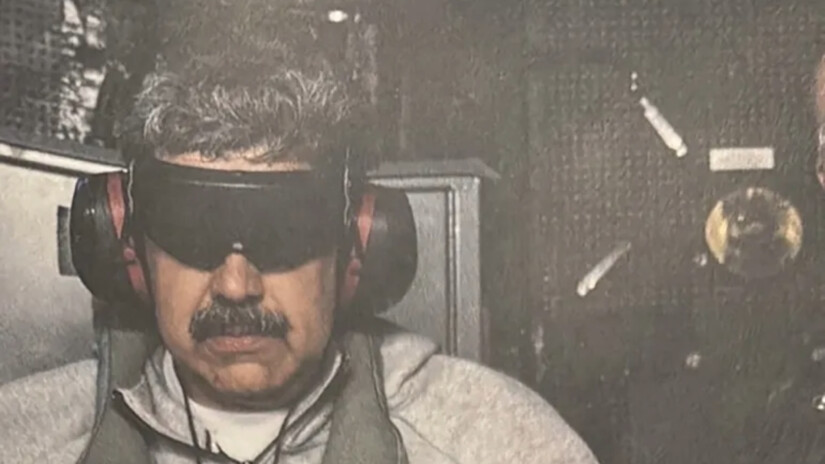

U.S. forces capture Maduro and take a picture as proof of life in a January 2-26 raid inside the country of Venezuela.

U.S. forces capture Maduro and take a picture as proof of life in a January 2-26 raid inside the country of Venezuela.According to Reuters, the U.S. military captured Maduro in an operation the Trump administration described as a law enforcement mission tied to criminal charges.

Critics argue it violated international law, which generally prohibits the use of force except in self-defense or with U.N. Security Council authorization. Supporters point to precedents like the U.S. capture of Panama’s Manuel Noriega, and to the claim that Maduro’s alleged criminality makes the action different.

Those arguments are now being aired at the United Nations, and they matter because they shape what other powers believe they can do, and what they believe they can justify.

Meanwhile, Venezuela’s leadership question did not resolve cleanly.

Delcy Rodríguez has been sworn in as interim president, in a transition described as being backed by the state’s ruling apparatus and shaped by the realities of who controls institutions and security forces. Russia, a Maduro ally, condemned what it called foreign aggression and backed Rodríguez.

Opposition leader María Corina Machado, recently awarded the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize, has presented herself as the democratic alternative and has rejected Rodríguez’s legitimacy.

If you are looking for clarity, this is what you have instead: a power vacuum filled by competing claims, foreign influence, and institutions that were built to prevent exactly this kind of transfer.

Maduro is not Chávez, but he governed in the shadow of Chávez, and the shadow hardened into a structure.

From 2013 onward, the pattern was consistent:

Whether you see him primarily as a dictator, a besieged anti-imperialist, a corrupt patron, or a political survivor depends on which causal story you believe and which harms you weigh most.

But there is one point that is difficult to escape: under Maduro, Venezuela stopped producing outcomes that most Venezuelans and much of the world could agree were legitimate, and that delegitimization became the country’s central engine of instability.

The temptation, after an event as dramatic as a capture, is to assume the hard part is over.

Venezuela suggests the opposite. The hard part begins when the cameras leave.

Here are the pressure points to watch:

Maduro’s rise began as a promise to continue a revolution. It ended, at least for now, as a test case for how far states will go when diplomacy fails, when sanctions stall, and when legitimacy collapses.

And Venezuela is still living with the consequences of all three.

This article is from TheMinuteman.org, Morristown Minute's new partner site: Bringing Meaning Back to the News.