Image

Two ballots in Bergen County, and a national story that will not die.

From THEMINUTEMAN.ORG - On Thursday morning, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in New Jersey posted a press release with a headline built for a political cycle: two “aliens,” prosecutors say, voted illegally in the 2020 federal election.

“Alien” is now commonly considered a derogatory term for a foreign-born person and has very negative connotations.

“Alien” is now commonly considered a derogatory term for a foreign-born person and has very negative connotations.The cases involve two Bergen County men, Muhammad Muzammal, 37, and Muhammad Shakeel, 62. A federal grand jury returned separate indictments, according to the press release. Prosecutors allege that both men were not U.S. citizens when they registered to vote in New Jersey, but certified on registration forms that they were citizens anyway. After their registrations were approved, the indictments say, each cast a ballot in the November 2020 general election, which included the presidential race.

Then, the government says, each man applied for U.S. citizenship and told a second story. On their naturalization applications, and later under oath in interviews with an immigration officer, prosecutors allege they falsely claimed they had never registered or voted in any election.

If convicted, the men face up to 1 year in prison for “voting by an alien in a federal election,” plus up to 5 years and up to 10 years on two separate false-statement counts tied to naturalization, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office. (The release notes that indictments are allegations and defendants are presumed innocent unless proven guilty.)

These are real cases with real stakes. They are also, in a country of more than 150 million presidential ballots, exactly the kind of rarity that gets used to tell an exaggerated story.

For nearly a decade, Donald Trump and allies have argued that illegal voting by noncitizens is widespread enough to threaten election outcomes. Trump advanced an evidence-free claim after the 2016 election that millions voted illegally. He later created a federal “election integrity” commission that became mired in controversy and was disbanded without producing proof of the sweeping fraud narrative its existence implied.

The Explosive History of the MAGA Slogan—America’s Most Divisive Battle Cry

The Explosive History of the MAGA Slogan—America’s Most Divisive Battle CryAfter Trump lost in 2020, allegations of a “stolen” election metastasized into a broader story about rigged systems, corrupted vote counts, and ineligible voters. Courts, state officials, and Trump’s own Justice Department repeatedly undercut that narrative, including then–Attorney General William Barr’s statement that DOJ had not found fraud on a scale that could change the outcome.

At the same time, Trump’s own administration’s cybersecurity and election-security apparatus took the unusual step of publicly rebutting claims of manipulated results. CISA and its election infrastructure partners said there was no evidence voting systems deleted or changed votes and described 2020 as the most secure election in American history.

The result is a weird dynamic that keeps repeating:

To understand why the New Jersey cases matter, and why they do not prove what political messaging often suggests, you need the mechanics.

The DOJ’s narrative, as laid out in the press release, is not that New Jersey’s 2020 election was flooded with illegal ballots. It is that two individuals allegedly made false statements at two separate choke points in the system:

That second step is important because it hints at how cases like this are often discovered. Naturalization is an intensive process with sworn statements, document checks, and interviews. When someone has voted illegally, the paper trail can collide with the citizenship application later.

The press release also highlights something most people miss in the political shouting: the harshest exposure here is not the act of voting itself. DOJ lists the voting count as a maximum of one year. The larger potential sentence comes from alleged false statements connected to naturalization.

One more note for readers tracking details: the DOJ release says Shakeel’s initial appearance is scheduled for January 21, 2025, even though the release is dated January 8, 2026, and says the indictments were returned December 22, 2025. That date appears internally inconsistent, and DOJ has not corrected it in the text as published.

The DOJ’s narrative, as laid out in the press release, is not that New Jersey’s 2020 election was flooded with illegal ballots.

The DOJ’s narrative, as laid out in the press release, is not that New Jersey’s 2020 election was flooded with illegal ballots.It depends on what you mean by “issue.”

If you mean “does it happen at all?”: yes. The New Jersey indictments are one example, and other cases exist around the country.

If you mean “is it common enough to swing federal elections?”: the best available evidence says no.

Multiple reviews and studies have found noncitizen voting to be extremely rare, often measured in tiny fractions of overall ballots. The Brennan Center has compiled evidence and research reaching that conclusion, and Migration Policy Institute has similarly noted there is no evidence of noncitizens voting in significant numbers in federal or state elections.

Even data from the conservative Heritage Foundation’s election fraud database, which is frequently cited to argue the system is vulnerable, is explicitly described by Heritage itself as a “sampling” rather than a comprehensive count. And reporting that dug into Heritage’s own Texas entries found they did not show a widespread noncitizen-voting problem.

That is the core tension: rare events can be real and still be politically misused. In a large electorate, you can always find a handful of cases. The question is scale.

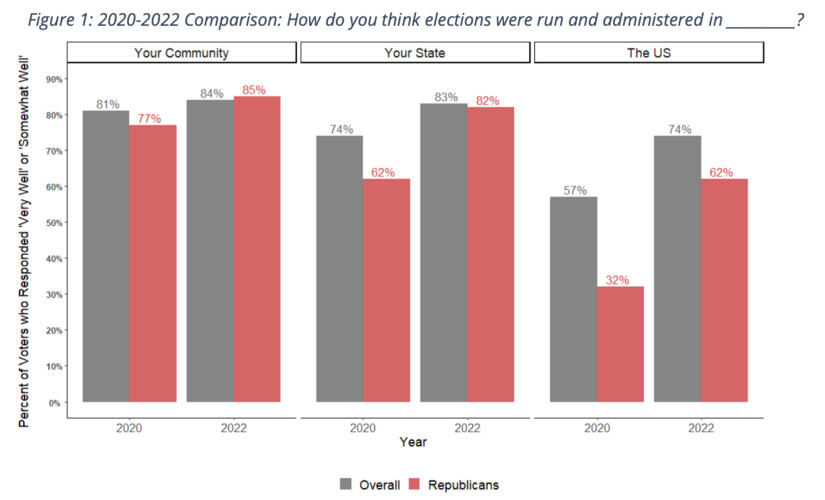

Confidence in Election Administration and Results. [The Center for Election Innovation & Research]

Confidence in Election Administration and Results. [The Center for Election Innovation & Research]Noncitizen voting is already illegal in federal elections, and it is illegal in state elections across all 50 states. New Jersey’s own voter registration rules require U.S. citizenship and reference statutory eligibility requirements.

So why doesn’t it happen more?

A simple answer is incentives. For many noncitizens, the downside risk is enormous. Voting illegally can jeopardize immigration status and future citizenship applications, and it creates a document trail that may surface later, as the New Jersey cases suggest.

Another answer is that election administration is built around multiple points of friction: sworn attestations, data checks, signature verification in many contexts, and post-election audits. These systems are not perfect, but they are designed so that large-scale fraud is hard to pull off without detection.

There is also a mundane reality: many suspected “noncitizen voting” controversies turn out to be data mismatches. People become citizens after being flagged. Records are outdated. A name match is not proof of illegal voting. When states have tried broad sweeps, they have sometimes wrongfully flagged eligible voters.

Because the allegation is politically useful.

It links two powerful themes, immigration and election legitimacy, and it can be invoked without needing to prove much. In 2024, House Republicans pushed federal legislation, including the SAVE Act, framed as a way to prevent noncitizens from voting in federal elections, even though that is already prohibited.

Supporters argue measures like proof-of-citizenship requirements are common-sense safeguards. Critics argue they can create new barriers for eligible citizens who do not have documents readily available, and they point out that the underlying problem is statistically tiny.

That is how a New Jersey press release about two alleged illegal ballots can become, by the weekend, a social media “proof” that 2020 was stolen.

It is not proof of that.

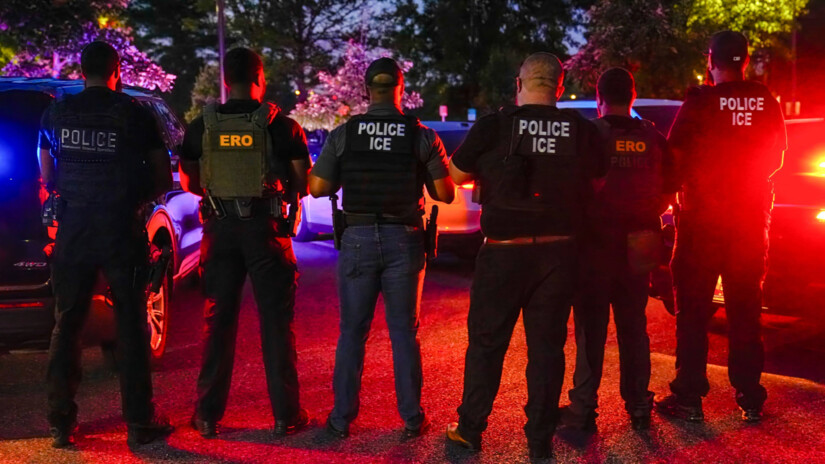

ICE and the Immigration Equation: How Targeted Priorities Can Restore Trust—and Strengthen a Country Built by Newcomers

ICE and the Immigration Equation: How Targeted Priorities Can Restore Trust—and Strengthen a Country Built by NewcomersIf you want to claim a national presidential election was stolen through noncitizen voting, you need evidence that noncitizen voting occurred at a scale large enough to overcome the certified margins in the states that determined the Electoral College result.

That is not what the New Jersey indictments allege. They allege two ballots.

More broadly, post-election litigation and official reviews did not produce proof of systemic fraud sufficient to change the outcome. The Trump campaign and allies lost the overwhelming majority of their court challenges. Trump’s own Justice Department leadership said it did not find fraud that could change the result. And election security officials in his administration said there was no evidence that voting systems deleted or changed votes.

You can hold two ideas at once:

Both can be true, and the country does itself a disservice when it treats the first as proof of the second.

NJ Voting Machines

NJ Voting MachinesNew Jersey is a useful lens because it shows how “election integrity” debates play out at the ground level, where the work is administrative and often unglamorous.

New Jersey also sits near major media markets where stories travel fast and mutate faster. A Bergen County case becomes a national meme within hours, stripped of context, weaponized as “see, they admitted it.”

They did not admit that.

They charged two people.

The DOJ press release is newsworthy for New Jersey because it shows federal prosecutors are willing to bring real cases when they believe illegal voting occurred, and because it underlines the serious consequences that can follow from false attestations and false statements in the naturalization process.

It is also newsworthy for the country because it demonstrates how misinformation ecosystems work: a rare event becomes a blanket story about legitimacy, and legitimacy becomes a lever for changing the rules of voting.

If you want election integrity, the hardest work is usually not in viral accusations. It is in the boring stuff:

clean records, transparent audits, well-trained poll workers, secure systems, and enforcement that is targeted, provable, and proportionate to the actual problem.

That is the difference between protecting a democracy and marketing distrust in it.

This article is from TheMinuteman.org, Morristown Minute's new partner site: Bringing Meaning Back to the News.